| |

STORY BEHIND THE DISCOVERY OF MORTON’S ETHER |

| |

UNKNOWN STORY BEHIND THE PAINFUL DISCOVERY OF MORTON’S ETHER |

| |

The troubled life and death of William Thomas Green Morton has been described in several texts. His first public demonstration of ether anesthesia was the highpoint of a life that was less than successful in many of his endeavors. |

| |

There are many mysteries surrounded in Morton’s life are much exploited by the historians. But the paper written by Mrs. Morton's, Elizabeth Whitman “The discovery of anaesthesia” McClvire's Mag., September 1896 tells a different story about Morton. |

| |

|

| |

Morton’s Adolescence |

| |

According to the historians: |

| |

Very little information is available about Morton’s childhood. |

| |

Morton was born August 9, 1819, in Charlton, Massachusetts. During his teenage years, his parents sold their farm and home in order to start a dry goods store. Unfortunately, the enterprise was not successful and the family’s financial circumstances forced Morton to quit school and take up work as a laborer in a tavern in Worcester, Massachusetts, at the age of 16 or 17 yr. Here, he was caught stealing money and was sent away from Worcester on the sheriff’s order to never return. |

| |

In 1836, at the age of 17, Morton moved to Rochester, New York, and found a job at a dry goods store. Two years later, he formed a partnership with Loran Ames in the dry goods business. Within 4 months, the partnership dissolved because Morton was caught passing bad checks and making phantom entries in the order books. He ran the business under his own name, but within 3 months he was in debt. Becoming desperate, he secured a loan from Phineas Cook, a businessman, but did not repay the borrowed funds and was compelled to leave Rochester for Cincinnati, Ohio. He also left behind a fiance´e from a prominent family and an unpaid bill at the Seward Academy, a private school where he had enrolled his sister, having brought her to Rochester. He was also excommunicated from his church for “dishonesty to his fellowman.” |

| |

In Cincinnati, he continued the same pattern of behavior, falsifying receipts in a dry goods partnership with Charles Pomeroy. Within a year, he departed, leaving behind another fiance´e. He managed to acquire a set of U.S. Mail seals which he used to backdate forged promissory notes to dupe his creditors. Over the next 2 yr, he moved from St. Louis, Missouri, to New Orleans, Louisiana, to Baltimore, Maryland, and finally on to Washington, D.C., where he continued to embezzle in the dry goods business until he was discovered. |

| |

But according to Mrs.Elizabeth Whitman Morton from “The discovery of anaesthesia”, |

| |

| My husband, whose full name was William Thomas Green Morton, was born in Charlton, Massachusetts, August 19, 1819. The family house stood on a farm of about one hundred acres, and was an old- fashioned wooden structure with an immense stone chimney in the centre. It was shaded by old trees, and covered by creepers and climbing plants. It was a New England farm-house. He studied in the schools of his native town and at the neighboring academies of Leicester and Northfield, where he studied hard for three years, leaving at the age of seven teen, when he went to Boston to begin earning his living. |

|

|

| |

Here he gained employment in the publishing house of the editor of the “Christian Witness, “James B. Dow. Uncertain what to do and homesick, he went back to his father's house in Charlton. He then concluded to study dentistry, which at that time had attained the dignity of a respected profession. |

| |

Adulthood, Dentistry, and the Use of Ether |

| |

According to the historians: |

| |

In 1842, Morton returned to Charlton, Massachusetts, and took up residence on land owned either by his late father or a relative. He met Dr. Horace Wells, from whom he learned the practice of dentistry and set up an office in Farmington, Connecticut. Wells and Morton also set up an office in Boston, Massachusetts, but the partnership failed after 4 months because of financial irregularities by Morton. |

| |

In Connecticut, he made the acquaintance of Elizabeth Whitman, whose wealthy family preferred a physician over a dentist as a husband for Elizabeth. In order to upgrade his social status and win approval from Whitman’s family, Morton contacted Dr. Charles Jackson in Boston to study medicine at the Massachusetts Medical College of Harvard University. Morton began his studies, but after marrying Whitman, he did not pursue the study of medicine any further. However, he did continue to consult with Jackson on the use of ether and how to administer it. On September 30, 1846, he performed a successful dental extraction under ether anesthesia. |

| |

But according to Mrs.Elizabeth Whitman Morton from “The discovery of anaesthesia”, |

| |

| His success was rapid. In 1844, two years after his graduation at the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery (the first dental college established in America), he was earning from his profession an income of about ten thousand dollars, being already recognized as one of the most skilful dental surgeons in Boston. |

|

|

| |

He had established himself in Boston a little before our marriage, I being a young girl of seventeen, just out of Miss Porter's school at Farmington, Connecticut, where my father lived. For a year before, Dr. Morton had paid me attentions, which were not well received by my family, he being regarded as a poor young man with an undesirable profession. I thought him very handsome, however, and he was much in love with me, coming regularly from Boston to visit me. Dr. Morton was one of those tremendously earnest men who believe they have a high destiny to fulfill. |

| |

During our early married life, while he was making himself known as one of the most skilful dentists in Boston and carrying on an enormous business, he found time in addition to pursue his medical studies at the Harvard Medical School, in order to take a medical degree, for he had promised my mother to give up dentistry. After the first successful use of the sulphuric ether, the immense responsibilities that came upon him, and the unceasing anxiety and annoyances, compelled him to give up the study of medicine and devote himself to anesthesia. |

| |

Every spare hour he could get was spent in experiment. He used to make experiments nearly every day on " Nig," a black water-spaniel, a good sized dog that had belonged to his father. |

| |

As he began to near success I became alarmed, for, not satisfied with trying the ether on bugs and animals, my husband began experimenting upon himself. He sent out his assistants offering a reward of five dollars to any person who would have a tooth drawn while under the influence of his pain-annulling agency. There were many people suffering from aching teeth which needed to be extracted, and the five dollars was an object; but no one could be induced to take the risk. |

| |

My husband, with characteristic persistence, at once procured a supply of pure ether, and, un willing to wait longer for a subject, shut himself up in his office, and tested it upon himself, with such success that for several minutes he lay there unconscious. That night he came home late, in a great state of excitement, but so happy that he could scarcely calm himself to tell me what had occurred; and I, too, became so excited that I could scarcely wait to hear. At last he told me of the experiment upon himself, and grew sick at heart as the thought came to me that he might have died there alone. |

| |

First successful administration of ether by Morton |

| |

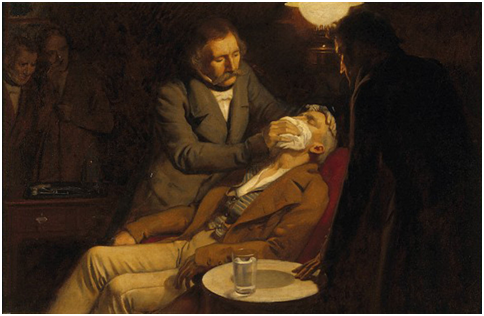

|

| |

Discouraged, he was on the point of etherizing himself once more, and having one of his assistants extract a tooth from his own head, when there came a faint ring at the bell. It was long past the hour for patients, but there stood a man with his face all bandaged and evidently suffering acute pain. And strangest of all were his words. |

| |

"Doctor," he said, "I have the most frightful toothache, and my mouth is so sore I am afraid to have the tooth drawn. Can't you mesmerize me ? |

| |

The doctor could almost have shouted with delight, but, preserving his self-possession, he brought the man into his office and told him he could do something better than mesmerize him. Then he explained his purpose of administering the sulphuric ether, and the man eagerly consented. Without delay my husband saturated a handkerchief with ether, and held it over the man's face, for him to inhale the fumes. The assistant, Dr. Hayden, who held the lamp, trembled visibly when Dr. Morton introduced the forceps into the mouth of the man and prepared to pull the tooth. Then came the strain, the wrench, and the tooth was out, but the patient made neither sign nor sound; he was quite unconscious. |

| |

Dr. Morton was overjoyed at the result. Then, as the man continued to make no movement, he grew alarmed, and it flashed through his mind that perhaps he had killed his patient. Snatching up a glass of water, he emptied it full into the face of the unconscious man, who presently opened his eyes and looked about him in a bewildered way. |

| |

“Are you ready now to have the tooth out?” asked the doctor. |

| |

“I am ready," said the man. |

| |

"Well, it is out now," said the doctor, pointing to the tooth lying on the floor. |

| |

“No!” cried the man in greatest amazement, springing from the chair, and, being a good Methodist, shouting, "Glory! Hallelujah!" |

| |

From that moment Dr. Morton felt that the success of sulphuric ether was assured. |

| |

Events Surrounding Ether Day |

| |

According to the historians: |

| |

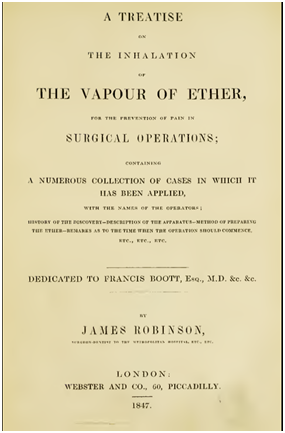

After this success, Morton inquired about the possibility of patenting a new process using sulfuric ether. He received an uncertain response, but was assured that a definitive answer could be provided by consulting the law. Morton then approached John Collins Warren, head of the surgical staff at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), about a public demonstration. |

| |

Hoping for a patent and fearing piracy, he refused to disclose his exact preparation. Warren had ethical misgivings because the preparation’s identity and safety were unknown. Despite misgivings, Warren had an invitation sent to Morton written by one of the junior house officers, perhaps reflecting Warren’s skepticism and reservations. |

| |

|

| |

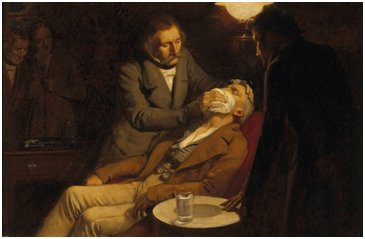

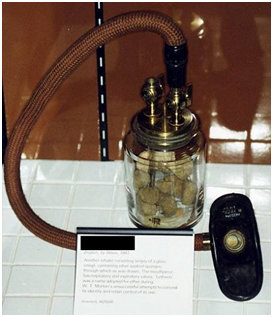

Morton’s demonstration was scheduled for October 16, 1846. The operating theater was full and skepticism was pervasive. The hour for the operation arrived and Dr. Morton was not on hand. Five minutes passed, ten minutes, and then Dr.Warren, the eminent surgeon, looking around with a smile on his face, slightly sarcastic, suggested that, as Dr. Morton was not present, it might be well to let the operation go on in the usual way'. The patient had meantime been brought in, and was lying on the operating-table deathly white, doubly apprehensive of what was to come. At that moment Dr. Morton came in, breathless from haste, carrying the inhaler, which had just been delivered to him by the maker and had nearly been the cause of the failure of the test. |

| |

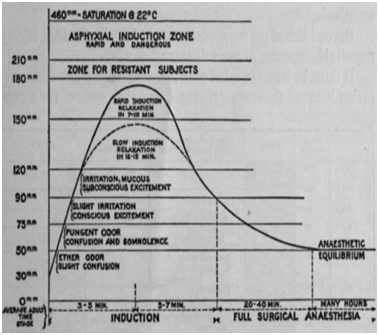

Without any delay, and with a coolness and self-possession in strong contrast with the general nervous tension of the assembly, Dr. Morton proceeded to administer sulphuric ether to a human being, for the purpose of destroying pain by forced anaesthesia in a surgical operation, for the first time in the world's history. Pouring the liquid into the inhaler, he lifted the latter to the patient's nostrils, and held it there for some minutes, allowing the man to breathe the fumes. Then, looking into his face intently, and feeling the pulse, he turned to Dr. Warren, who stood near with his surgeon's knife behind him, and said, in a quiet tone that sounded plainly through the silence: |

| |

“Your patient is ready, doctor." |

| |

Then in all parts of the amphitheatre there came a quick catching of the breath, followed by a silence almost deathlike, as Dr. Warren stepped forward and prepared to operate. The sheet was thrown back, exposing the portion of the body from which a tumor was to be removed, an operation exceedingly painful under ordinary conditions, although neither very difficult nor very dangerous. The patient lay silent, with eyes closed as if in sleep; but everyone present fully expected to hear a shriek of agony ring out as the knife struck down into the sensitive nerves. But the stroke came with no accompanying cry. Then another and another, and still the patient lay silent, sleeping, while the blood from severed arteries spurted forth. The surgeon was doing his work, and the patient was free from pain, so it seemed at least; and all in wonder strained their eyes and bent forward, following eagerly every step in the operation. Those in the front rows leaned far over or knelt on the floor, so that those behind might see well. The operation advanced quickly and easily to its finish. The tumor was taken away, the arteries fastened with ligatures, the gaping wound sewed up, then dressed and bandaged. Half an hour covered the whole of it. During that time no cry or groan escaped the patient, no indication of suffering. |

| |

Dr. Morton aroused the patient after the operation was completed, and said, "Did you feel any pain?" The patient replied, “No." Then Dr. Warren, turning to the company, said in his impressive manner, "Gentlemen, this is no humbug." |

| |

All pressed about Dr. Morton and congratulated him upon his success. |

| |

According to Mrs.Elizabeth Whitman Morton - Events Surrounding Ether Day from “The discovery of anaesthesia” |

| |

The night before the operation, my husband worked until one or two o'clock in the morning upon an inhaler he had devised, and then regarded as essential to the operation, although it has since been discarded. I assisted him. |

| |

I had been told that one of two things was sure to happen: either the test would fail and my husband would be ruined by the world's ridicule, or he would kill the patient and be tried for manslaughter. |

| |

After resting a few hours, Dr. .Morton was off early in the morning to see the instrument maker, for there were still changes necessary in the inhaler. 'From that moment I saw nothing of him for twelve hours, which were hours of mortal anxiety. |

| |

How they dragged along as I sat at the window, expecting every moment some messenger to tell me that the patient had died under the ether and that the doctor would be held responsible! Two o'clock came, three o'clock, and it was not until nearly four that Dr. Morton walked in, with his usually genial face so sad that I felt failure must have come. He took me in his arms, almost fainting as I was, and said tenderly: “Well, dear, I succeeded." |

| |

After Ether Day |

| |

According to the historians: |

| |

The next 21 yr of Morton’s life were spent attempting to gain official recognition and financial reward for his demonstration of ether as an anesthetic. Morton petitioned Congress on several occasions, beginning in 1849, for a sum of $100,000 to compensate him for his achievement. These attempts were unsuccessful despite the backing of the surgeons at MGH. He also petitioned the French Academy of Sciences for recognition, but the Academy awarded the credit jointly to him and to Charles Jackson. The State of Connecticut legislature recognized Horace Wells as the founder of etherization. In June 1868, Atlantic Monthly magazine recognized Jackson as the primary developer of the use of ether as an anesthetic. The next month, Morton traveled to New York to prepare a rebuttal, but during his stay he probably developed heat stroke and succumbed on July 15, 1868. |

| |

According to Mrs.Elizabeth Whitman Morton - Events after Ether Day from “The discovery of anaesthesia” |

| |

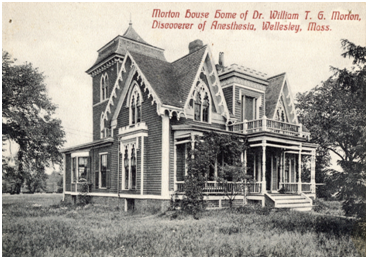

In spite of various efforts that were made during subsequent years to obtain recognition from the United States government of Dr. Morton's services to the country and to the world, nothing was ever done. This was, perhaps, the greatest sorrow of my husband's later years, a sorrow rendered all the more keen from the fact that other governments hastened to bestow upon him orders and decorations. Russia gave him the “Cross of the Order of St. "Vladimir; " Norway and Sweden gave him the " Cross of the Order of Vasa;" and the French Academy of Arts and Sciences sent him a gold medal, the Montyon prize. |

| |

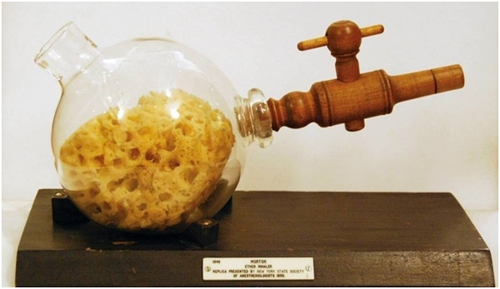

What he regarded as his greatest treasure was a small silver casket containing one thousand dollars in money, and presented by the trustees of the Massachusetts General Hospital. This was given “in honor of the ether discovery, September 30, 1846." The casket, medal, and decorations are now in the Historical Rooms in Boston, as well as many original documents relating to the discovery, the medal, and the orders. |

| |

Last days of my husband's life - Mrs.Elizabeth Whitman Morton |

| |

On July 6, 1868, he left Etherton Cottage for New York, to reply to an article that had recently appeared in one of the monthlies advocating Dr. Jackson's claim to be the discoverer of sulphuric ether. |

| |

The weather was very hot, and on July 11 he telegraphed me that he was ill and wished me to come to him. I went at once, and found he was suffering with rheumatism in one leg. Under the treatment of the distinguished Dr. Sayre, my husband improved, and on Wednesday, after dinner, he proposed we should drive to Washington Heights and spend the night there at the hotel, as a change from the hot city. We started about eight o'clock in the evening. Dr.Morton himself was driving. |

| |

After a little he complained of feeling sleepy, but refused to give me the reins or to turn back. Just as we were leaving the Park, without a word he sprang from the carriage, and for a few moments stood on the ground, apparently in great distress. Seeing a crowd gathering about, I took from his pocket his watch, purse, also his two decorations and the gold medal. Quickly he lost consciousness, and I was obliged to call upon a policeman and a passing druggist. |

| |

Dr.Swann, who assisted me. We laid my husband upon the grass, but he was past hope of recovery. We sent at once for a double carriage, but it was an hour before one came. Then two policemen lifted him tenderly upon the seat, I being unable to do anything from the condition I was in: the horror of the situation had stunned me, finding myself alone with a dying husband, surrounded by strangers, in an open park at eleven o'clock at night. |

| |

We were driven at once to St. Luke's Hospital, where my husband was taken in on the stretcher, and immediately the chief surgeon and house physicians gathered about him. At a glance the chief surgeon recognized him, and said to me: “This is Dr. Morton ?" |

| |

I simply replied, “Yes." |

| |

After a moment's silence he turned to the group of house pupils, and said: |

| |

“Young gentlemen, you see lying before you a man who has done more for humanity and for the relief of suffering than any man who has ever lived." |

| |

In the bitterness of the moment, I put my hand in my pocket, and taking out the three medals, laid them beside my husband, saying: "Yes and here is all the recompense he has ever received for it." |

| |

|

| |

Dr. Morton died at the age of forty-eight. He was buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, near Boston, in the presence of many noted physicians of Boston. Over his grave stands a monument erected by the citizens of Boston, with this inscription, written by the late Dr. Jacob Bigelow of Boston: |

| |

“William T. G. Morton, Inventor and Revealer of Anaesthetic Inhalation.

By whom pain in surgery was averted and annulled.

Before whom in all time surgery was agony.

Since whom science has control of pain."

|

| |

References : |

| |

1. Ramon F. Martin, M.D., Ph.D., Ajay D. Wasan, M.D., M.Sc. Sukumar P. Desai, M.D., An Appraisal of William Thomas Green Morton’s Life as a Narcissistic Personality. Anesthesiology: July 2012 - Volume 117 - Issue 1 - p 10–14. |

| |

2. MORTON, Elizabeth Whitman The discovery of anaesthesia. McClvire's Mag., September 1896. YALE MEDICAL LIBRARY. HISTORICAL LIBRARY. |

| |

3. Triumph Over Pain: The Curiously Contentious History of Ether. Daniel J. Kim. UWOMJ 78(1)2008 P91 |

| |

4. Ames LJ: Affidavit April 11, 1849. Boston: Charles T. Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

5. Cook PB: Letter to Joseph L Lord, April 7, 1849. Boston: Charles T. Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

6. Seward JW: Affidavit, April 9, 1849. Boston: Charles T. Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

7. Dickey D, Clerk of the Brick Church: Copy of Records from the Brick Church of Rochester, NY, April 15, 1849. Boston: Charles T. Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

8. Creagh J: Affidavit, April 28, 1949. Boston: Charles T Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

9. Riggs G: Deposition, September 28, 1849. Boston: Charles T Jackson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society |

| |

10. Eddy RH: To the Surgeons of the Massachusetts General Hospital, “The Ether Discovery.” Littell’s Living Age 1848; 201:546 |

| |

11. Whitman F: Affidavit, “The Ether Discovery.” Littell’s Living Age 1848; 201:534 |