Conference Lectures

SIMULATION TRAINING IN ARMED FORCES MEDICAL SERVICES

- Dr. (Maj) D V Bhargava, MD DNB

Anaesthesiologist, Indian Army

Introduction

In a hospital . . .

Dr. A: Tourniquet is in place, bleeding has stopped. The “C” problem has been solved for now. So let’s start at “A”.

Dr. B: He is breathing, albeit shallow and fast; Apply oxygen mask to face.

“10 litres per minute” is the instruction to the paramedic.

Dr. A: No audiblebreathing on the left, the neck veins are swollen

The alarm draws the rescue team’s attention to the monitor.

Heart rate 160/minute.

Dr. B: Pulses hardly detectable. Needle thoracostomy in 2nd ICS left.

The patient stabilises.

“Thank you!” it sounds from the loudspeaker – “the simulation is now completed.”(1)

A modern teaching tool – Simulation Based Medical Education (SBME)

Simulation is a technique to replace or amplify real patient experiences with guided experiences, artificially contrived, which evokes or replicates substantial aspects of real world in a fully interactive manner (2).

Eduard Lindeman (1885-1953) who is considered to be a major philosopher of adult education in the United States put forward his strong belief, way back in 1927 that “experience is the adult learner's living textbook”. He advocated for the use of adult learning groups, believing that "adult education must be confined to small groups and that lectures and mass teaching should be automatically eliminated" The rebirth of many of Lindeman's ideas are evident in different areas. Community-based programs, rejecting traditional curriculum, are using the learners' experiences to write new learner-centred lessons and curriculum. Instructors are learning to facilitate learning groups, moving away from the concept that knowledge comes from the teacher, not the students(3).

Medical simulation is an invaluable application where distinct advantages include clear objective learning without compromise in patient safety, augmented focus on learning and unlimited repetitive access to clinical scenario. Technological advancements in the field of biomedical engineering and technology have challenged the sceptical thinking that medical science and related skills are too complex to be simulated accurately. Computers facilitated the mathematical description of human physiology and pharmacology, worldwide communication and the design of virtual world (4).

SBME can be used for “in the classroom” learning as well as “on the field” or “live fire” exercises. Adobe Flash based medical animation videos are available for basic understanding of pathophysiologic processes. The “live fire” exercises can range from a simple act in an immersive environment (Ex: Operation Theatre instead of a Classroom) to a significant invention like the Combat Trauma Patient Simulator (CTPS) system.

Simulation and Military Medicine

Advancement in technology, lessons of benefit from flight simulation, improvement in plastics and resuscitation science were precursors to medical simulation. Simulation was very popular in the aviation industry due to the invention of Link trainer for flight simulation in early 1930s (5, 6). Simulation software like Surgeon (1986), as reported by Computer Gaming World (7), were successfully able to simulate operating on an aortic aneurysm on Apple McIntosh. Medical simulation began to be possible and partly affordable due to ideas originating from various indigenous and innovative methods of military medical training. This has led to augmented funding, increased interest in further development of simulation software and advances in biomedical engineering along with the vital knowledge base for understanding of disease and lifesaving therapy.

Simulation is likely to have an imposing role in Military medicine. The major drive behind the transfer of modelling and simulation technology to medicine is the military. The initial impetus provided by the military was later taken over by the gaming industry due to development of high resolution graphics (8). Scepticism, lack of communication and burden of proof are considered the three major reasons for slow progress (9). Widespread acceptance of standardised patients, virtual reality and mannequins have occurred in the past decade (10). The American Board of Emergency Medicine has adopted medical simulation technology for evaluation of students using specific “patient scenarios”. Military medicine can be considered similar to Emergency Medicine in certain aspects and unique in few other additional areas.

However, concrete evidence for the use of simulation in military medicine is still not unfurled completely. It is felt that validity will always be intangible and medical fraternity must start to accept simulation on the basis ofconfidence from aviation industry (11). Evidence supporting a positive impact on patient safety and quality of care as a consequence of simulation training is neither available nor conclusive. A recent questionnaire based study by David Powers and colleagues (12) among defence personnel undergoing training in military medical care has found use of Simulators to have a positive response on learning.

Components of Simulation

Contemporary military trainers understandthat essential elements in combat trauma training are realism, human-specific injuries and treatments, volume of trauma exposure, and team building (13). These objectives can be effectively met by designing a course using high-fidelity medical simulation with immersive learning environments.The specific learning objectives in simulation training for an emergency situation like military trauma are (a) Crisis resource management – Crew resource management-The term originated in the aviation industry and was adopted in simulation training.(b) Team dynamics: Understanding of Team dynamics and improvement of team effectiveness. This specifically incorporates cross-specialty communication in addition to the existing core team dynamics. (c) Debriefing: Debriefing is considered the heart of a simulation session. Experience can be transformed into learning through reflection, and the facilitator is essential in this process (14). Debriefing maximises the learning that occurs as a result of simulated experience. However, literature describing the most appropriate methods for debriefing is not yet available (15).

Difference between Military and Civil treatment protocols

Military clinical protocols are distinctly different (16). These include early rapid use of blood and blood products, Damage Control Resuscitation, specialist anaesthetic and surgical equipment. The extent of trauma is unfamiliar along with unfamiliar environment and most feasible protocols. Another unique aspect is the constant turnover of manpower at regular intervals. This means that the whole medical system requires to be prepared to work in deployed austere environment while integrating newly arriving individuals. Hence, human factors play a very important role which include rapid repeated decision making about resuscitation or “right turn resuscitation”, assembling trauma team as per protocol without causing overload on certain individuals, carefully mobilising optimum amount of resources, interdisciplinary communication, cross-check and double-check and adhering to organisational policies and SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures). Deployment in environment with Chemical Biological Radiation Nuclear (CBRN) risk is another aspect which requires specific training.

Training requirements for operational environment:Training for operational environment is provided at number of levels. These include general individual based service specific pre-deployment training, several professional courses for acquiring specific skills (Ex: Battlefield Advanced Trauma Life Support Course (17), Tri-Service Anaesthetic Apparatus Simulation Course (18) etc.,) and macro-simulation exercises involving entire field hospital deployment (Ex: HOSPEX (19) of UK Army).

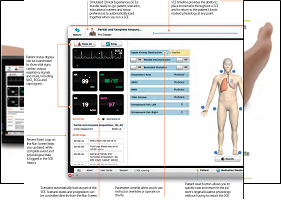

Simulation in the Armed Forces Medical Services – International - Classification of Simulators – Simulators employed for training in military medicine require certain specific attributes. Some examples areLaerdel Simman Military – (description with videos), Cut Suit Simulator– (description with videos), CaeserTM Point of Injury Trauma Care Simulator (Fig 1). It has been used for training at the NATO Centre of Excellence for Military Medicine in Budapest, Hungary.

Fig 1 CaeserTM Point of Injury Trauma Care Simulator.

In addition, the conventional simulators i.e., Part trainers and High fidelity trainers can be employed with certain modifications in “patient scenario”.

Existing simulation facilities all over the world: Multi-layered training requisites for military medicine are likely to be more effective when imparted by use of simulation tools.

- Germany: Clinical Simulation Centre at GE Armed Forces Hospital, Hamburg (1) is a simulation facility functional since last 10 years operated by the German Armed Forces Joint Medical Services. A patient simulator room has been installed in 2009 which offers courses for Germans medics as well as NATO forces as part of pre-deployment training.

- UK: A course (Military Operational surgery course) is conducted at the Simulation Suite at the Royal College of Surgeons where scenarios can be rehearsed with surgeons, anaesthetists and operating room practitioners.

- Defence Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRTI) (20): Defence Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRTI) is a tri-services organisation of the US Army providing training in joint medical readiness courses in Trauma Care, Burn Care, Disaster Care, Humanitarian assistance and CBRN preparedness/response.

- Combat Trauma Patient Simulator: The Combat Trauma Patient Simulator is used by the US Army. It encompasses Lockheed Martin MILES system, the Operational Requirements-based Casualty Assessment system (ORCA), the Jackson Medical Simulation library (JMSL), and the Human Patient Simulator (HPS). The MILES engagement simulator simulates gunfire and other combat engagements. This provides necessary understanding to medical trainee to begin the process into medical care without actual battlefield experience and actual casualties. The simulated casualties are moved to the next stage where the ORCA facilitates simulation for assessment of the severity of medical condition. Under the JMSL, all casualties generated by MILES and assessed initially by ORCA are sent through transition phases in order to accurately simulate a casualty progressing to a more and more deadly state while awaiting treatment under average circumstances. Training on the casualty management is done by use of HPS. The CTPS involves integration of all incompatible parts of CTPS process using a high level Architecture based system (21).

- NATO Centre of Excellence for Military Medicine in Budapest, Hungary. (MILMED COE): Accredited by NATO in 2009, it is an international military organisation with the core task to facilitate interoperability between the military medical services in NATO. MILMED COE facilitates capacity and capability building through interoperability by multinational standardisation pre-, during- and post-deployment (22).

Evidence regarding Simulation training in Trauma / Military Medicine:

Human patient simulator (HPS) has been in use since 1969 for teaching purposes. Recently, it has found its application in training for trauma resuscitation. Advanced Simulation technology has been used for training of military resuscitation teams of Australian Defence Force since 1999 (23). Holcomb and colleagues have validated the HPS as an effective teaching or evaluation tool by demonstrating the ability to evaluating trauma team performance in a reproducible fashion (24).

Simulation Based Medical Education - Indian experience

It is felt that there is some resistance to adopting simulators as a viable tool or technique of teaching-learning (25). The immediate challenges encountered before adopting simulators are lack of trained faculty for conducting simulation sessions, lack of role play and problem based teaching-learning methodology during formative years of medical training in addition to cost constraints (25, 26). In addition, systematic studies or experiences are missing in available literature. Simulation facilities are available in certain medical establishments (Ex: AFMC, Pune and JIPMER, Pndicherry). At JIPMER, Pondicherry, a high fidelity HPS (HPS 10, CAE Healthcare, Germany) is used for a 2 week orientation programme at the beginning of three year post graduate program in Anaesthesiology. About 90% of the course participants felt that the exercise was very useful (25).

Simulation training in Indian Armed Forced Medical Services

Doctors of Indian Armed Forces when actually involved in casualty management in an operational environment are required to be competent in basic trauma management irrespective of the specialty of practice in the hospital. The Indian Armed Forces have a multi-layered approach to training medical officers and paramedical staff in military medicine, specifically trauma management.

Training at Undergraduate level: Training for Medical Cadets with the use of part trainers is imparted in Basic Life Support (BLS) & Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) skills at AFMC as a part of their undergraduate curriculum in Anaesthesiology & Critical Care. Later, a refresher course in BLS, ACLS and basic trauma assessment & management is carried out at the beginning of Internship training at AFMC.

Training of Medical Officers: For Medical Officers, Trauma Life Support course capsule as part of Medical Officers Basic Course was carried out at Lucknow (27). For medical officers posted to the northern sector, a combat care capsule course was held at suitable zonal hospital. A simulation exercise about casualty evacuation in combat scenario is organised during the same training period. About 6 to 8 years later, a week long course on Trauma Life Support encompassing the principles of Initial trauma care is held as part of Medical Officers Junior Command Course (27).

Clinical Skills & Simulation Lab, AFMC: In June 2013, a Clinical Skills & Simulation Lab was inaugurated at AFMC, Pune. A total of 72 mannequins are laid out for undergraduate, postgraduate and paramedical training. Airway management simulator, Part trainers for BLS Skills, ACLS rhythm simulators, Endoscopy trainer, Bronchoscopy trainer, Lumbar puncture trainer, Epidural trainer and Labour simulator are available. A HPS (METI) simulator is available for simulation training on various emergency scenarios (28). Courses accredited by the American Heart Association (AHA) like BLS, ACLS are regularly conducted at the Clinical Skills & Simulation Lab by the Faculty of Department of Anaesthesiology & Critical Care, AFMC. Presently a 10 day capsule on BLS, ACLS and Trauma management for Medical Officers is carried out at regular intervals. Facilities at the Skills lab are utilised to train local school children and Traffic Police of Pune city in BLS skills.

Other service hospitals: Various service hospitals and field hospitals organise regular courses for paramedical staff at regular intervals as per laid out service policy. All zonal military hospitals have well-equipped Technical Training Schools where training in BLS, ACLS and Trauma management is imparted to paramedics (Armed Forces as well as Paramilitary forces, GREF etc.,) by the use of part-trainers by doctors of the same hospital.

Conclusion

Simulation technology is emerging as an important tool for training at various levels of medical education and is definitely improving outcome after a teaching-learning exercise. A variety of methodically plannedand innovative simulation techniques are being employed by Armed Forces all over the world to integrate simulation technology with training for a complex field like Trauma management.

References:

1. Michael Braun. Clinical Simulation Centre at the GE Armed Forces Hospital, Hamburg. Available at:http://www.mci-forum.com/category/experiences/420-clinical_simulation_centre_at_the_ge_armed_forces_hospital_hamburg.html. Accessed October 30, 2014.

2. Burt DE. Virtual reality in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1995;75:472-80.

3. Sarah Nixon-Ponder. Leaders in the Field of Adult Education: Eduard C. Lindeman. Available at:http//:literacy.kent.edu/Oasis/Pubs/0800-1.htm. Accessed November 01, 2014

4. Smith C, Daniel P. Simulation Technology: a strategy for implementation in surgical implementation and certification. Presence: Tele-operators and Virtual environments 2000:9.

5. The Link Trainer. Stark Ravings website. Available at: http://www.starkravings.cim/limktrainer/inktrainer.htm; 2007. Accessed October 30, 2007.

6. A brief history and lineage of our CAE-Link Silver Spring operation. Life after Link website. Available at: http://lifeafterlink.org/brochure.shtml; 2007. Accessed October 30, 2014.

7. Boosman, Frank (November 1986). "Macintosh Windows". Computer Gaming World. p. 42.

8. Strachan IW. Technology leaps all around propel advances in simulators. National defense: the business and technology magazine Web Site. Available at: http://www.national defensemagazine.org/index.cfm; 2000. Accessed October 28, 2014.

9. Buck GH. Development of simulators in medical education. Gesnerus 1991; 48:7-28.

10. Kathleen R Rosen. The history of medical simulation. J of Crit Care 2008: 23: 157-66.

11. Tarver S. Anesthesia simulators: concepts and applications. Am J Anesth 1999; 26:393-6.

12. David Power, Patrick Henn, David Hick, John McAdoo. An evaluation of high fidelity simulation using a human patient simulator in a new Diploma in Military Medical Care. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health. 2013; 21(4): 4-10.

13. Improving Military Medicine: Human-Based Training Methods. Available at: http://pcrm.org/research/edtraining/military/human-based-combat-trauma-training-methods. Accessed October 30, 2014.

14. Savoldelli G, Naik V, Park J, Joo H, Chow K, Hamsha S. Value of debriefing during simulated crisis management: oral versus video assisted oral feedback. Anesthesiology. 2006;105 :275-85.

15. McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ. A critical review of simulation-based medical education research:2003-2009. Med Educ 2010;44:50-63.

16. Hodgetts T, Mahoney PF, Byers M et al. ABC to <C>ABC. Redefining the military traum paradigm. Emerg Med J 2006;23:745-6.

17. UK Defence Medical Services. Battlefield Advanced Trauma Life Support. UK Defence Medical Services, 2008.

18. Houghton. The Triservice anaesthetic apparatus. Anaesthesia 1981; 35:1094-108.

19. Arora S, Sevdalis N. Hospex and concepts of Simulation. JR Army Med Corps 2008; 154:202-5.

20.DMRTI. Defence Medical Readiness Training Institute website. Available at: http://www.dmrti.army.mil/index.html. Accessed 01Nov 2014.

21. Petty, M. D., Windyga, P. S. A High Level Architecture-based Medical Simulation System. SIMULATION. 1999:73; 281-7.

22. NATO Centre of Excellence in Military Medicine MILMED COE website. Available at: http://www.coemed.hu/coemed/about-us. Accessed November 01, 2014

23. Hendrickse AD1, Ellis AM, Morris RW. Use of simulation technology in Australian Defence Force resuscitation training. J R Army Med Corps. 2001;147:173-8.

24. Holcomb, J.B., Dumire, R.D. Evaluation of Trauma Team Performance Using an Advanced Human Patient Simulation for Resuscitation Training. Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 2002:52; 1078-86.

25. Kundra P, Cherian A. Simulation based learning: Indian perspective. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2014;30:457-8.

26. Lateef F. Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:348-52

27. Gambhir RPS, Agarwal A. Training in Trauma Management. MJAFI 2010:66;354-6.

28. Armed Forces Medical College. Department of Anaesthesiology web site. Available at http://afmc.nic.in/Departments/Anaesthesiology/facilities.html. Accessed on 30Oct2014.