Conference Lectures

“Asthma is a chronic disorder of the airway in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread, but variable airflow obstruction within the lung that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment.”

Bronchospasm, the clinical feature of exacerbated underlying airway hyper reactivity has the potential to become an anesthetic disaster. During the peri-operative period bronchospasm usually arises during induction of anesthesia but may also be detected at any stage of the anesthetic course. Accordingly, prompt recognition and appropriate treatment are crucial for an uneventful patient outcome. Different triggers are identified in the occurrence of bronchospasm during induction with asthma, a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways frequently involved. The purpose of this clinical presentation is to discuss the key points of bronchospasm during induction.

Preoperative evaluation

A thorough history and physical examination provides the anaesthesiologist with information that allows for appropriate identification of level of disease, degree of symptom control, and anesthetic risk stratification. Review of baseline exercise tolerance, hospital visits secondary to asthma (including whether endotracheal intubation or IV infusions were required), allergies, and previous surgical/anesthetic history is essential.

Physical examination:

Physical examination should include vital signs and assessment of breath sounds, use of accessory muscles, and level of hydration. The presence of labored breathing, use of accessory muscles, and prolonged expiration time suggest poorly-controlled asthma. Wheezing on auscultation is concerning, particularly if the wheezing is noticed in phases of the respiratory cycle other than end-expiration.

The Anesthetic Plan:

The anaesthetic plan should balance suppression and avoidance of bronchospasm with the usual goals of patient safety, comfort, and a quiet surgical field. Choice of anaesthetic method must be tailored to the patient, the procedure, clinical assessment, and the preferences of all involved. No definitive evidence shows that one method is generally superior to another. It seems prudent to avoid direct instrumentation of the airway if at all possible, but anxiety or pain during regional anaesthesia (peripheral nerve or neuraxial block) could themselves precipitate an attack of bronchospasm. Clearly, the highest risk cases are those in which the airway itself is the subject of surgery, or surgery involving the thorax or upper abdomen where tracheal intubation cannot be avoided.

Preoperative preparation:

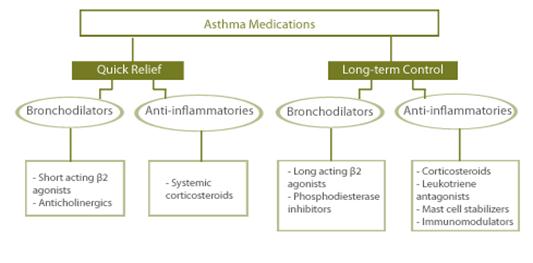

If evaluated far enough in advance, patient is advised to stop smoking 2 months before surgery; this will allow the recovery of mucocilliary clearance. Oral methylprednisolone 40mg for 5days before the surgery, given will decrease post intubation wheezing. If patient evaluated first time just before the surgery intravenous hydrocortisone can be useful. Short acting bronchodilator therapy given prophylactically has likely benefit. MDI or nebulizer delivery is equivalent if proper technique is used. Elective surgery should not be performed in the presence of active bronchospasm and the cause (e.g. a new respiratory infection) and symptoms should be actively treated until the patient is back to baseline status.

Premedication:

An optimal premedication allays anxiety, improves work of breathing, and possibly averts the induction of bronchospasm, while eschewing oversedation and respiratory depression. No ideal drug or drug combination exists for this. The α-2 agonist dexmedetomidine has a favourable profile, including anxiolysis, sympatholysis and drying of secretions without respiratory depression.

By drying secretions and suppressing upper airway vagal responses, anticholinergic agents such as atropine or glycopyrrolate can decrease airway reactivity and should be considered.

Monitoring:

Monitoring during induction in asthma includes pulse oxymeter, capnography, NIBP, ECG and arterial line (ABG). Choice of monitoring should be geared towards assessment of airway mechanics (volumes, pressures, airway flows, I:E ratio, compliance, respiratory waveforms if available). It is very useful to augment the end-tidal CO2monitoring with a visible waveform so that flattening of the capnogram can be used as an index of expiratory airway flow. However, as bronchospasm worsens, the End tidal CO2 to PaCO2 gradient widens. Consideration should always be given to placing an arterial line in high-risk cases to facilitate ABG measurement.

Intraoperative management :

Bronchospasm can be provoked by laryngoscopy, trachealintubation, airway suctioning, cold inspired gases, and trachealextubation. It is extremely important that patient should be deeply sedated prior to airway instrumentation. Whenever possible consider regional anesthesia. Intravenous lidocaine has been successfully used to decrease autonomic stress response to airway instrumentation. Anti-muscarinic agents such as glycopyrrolate may decrease secretions with added advantage of bronchodilatation.

Induction: Propofol is the induction agent of choice in hemodynamically stable patient. Ketamine is ideal for hemodynamically unstable asthmatic. Propofol appears to be superior to thiopental and etomidate in constraining increases in airway resistance. Volatile anesthetics are excellent choice for general anesthesia as they depress reflexes and produce direct bronchodilatation . Inadequate depth of anaesthesia at any point can allow bronchospasm to be precipitated. Anesthetic maintainance with a volatile agent such as isoflurane or sevoflurane confers protective bronchodilation. However, there is evidence that desflurane provokes broncho-constriction in smokers. Halothane has been favored in the past, but now is not as available, is more blood-soluble leading to longer induction times and in the setting of hypoxaemia or acidaemia could potentiate arrhythmias.

Warm, humidified gases should be provided at all times. Rapid sequence or standard induction should be performed as indicated as long as adequate anesthesia is assured;

Muscle relaxants: succinylcholine is not contraindicated. Neuromuscular blocking agents are the most common medications to cause allergic reactions in the operating theatre. Some agents, such as mivacurium and atracurium have histamine-releasing effects. Cisatracurium and vecuoronium does not cause histamine release or bronchospasm. Rocuronium is useful for the asthmatic who needs a rapid sequence intubation. Rapacuronium, a promising rapid onset neuromuscular blocker, was removed from the market because of its muscarinic receptor-mediated bronchospasmic effects.

Ventilation:The decision whether to intubate the trachea, provide anaesthesia by mask, or use a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is a clinical one. However, there is evidence that tracheal intubation causes reversible increases in airway resistance, not observed with placement of an LMA.

In selecting a ventilatory mode, attention should be given to providing an adequately long expiratory time to avoid the build-up of intrinsic or auto-PEEP. This can be facilitated by using higher inspiratory flow rates or smaller tidal volumes than usual. Patients should be kept adequately hydrated as usual, but fluid overload, pulmonary congestion, and edema can precipitate bronchospasm (‘cardiac asthma’).

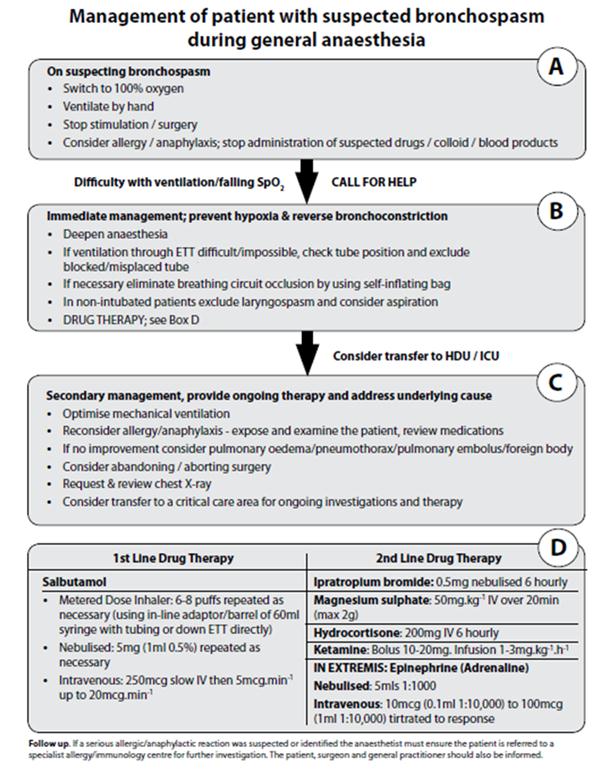

Acute intraoperative bronchospasm (Perioperative Bronchospasm)

Signs and symptoms of airway obstruction intraoperatively, consistent with bronchospasm include elevation of the peak inspiratory pressure, prolonged expiratory phase, and visible slowing or lack of chest fall, change in capnography (shark fin capnograph i.e. upsloping of curve)

The chest should be auscultated to confirm wheezing (and, if not accessible, the expiratory limb of the anaesthetic circuit). Diminished or absent breath sounds can be an ominous sign suggesting critically low airflow. The differential diagnosis includes mucous plugging of the artificial or native airway and pulmonary oedema. A unilateral wheeze suggests the possibility of endobronchial intubation, foreign body obstruction such as a dislodged tooth, or even a tension pneumothorax. If none of these conditions exists, or if bronchospasm persists after they have been corrected, a treatment algorithm for acute intra-operative bronchospasm should be instituted.

Treating Perioperative Bronchospasm

The aims of treatment are to relieve airflow obstruction and subsequent hypoxemia as quickly as possible. General Measures: When isolated perioperative bronchospasm occurs, oxygen concentration should be increased to 100%, and manual bag ventilation immediately started to evaluate pulmonary compliance and to identify all causes of high-circuit pressure. Increased concentration of a volatile anesthetic (sevoflurane, isoflurane) is often useful with the exception of desflurane because of its airway irritant effects, particularly in smokers.Deepening anesthesia with an intravenous anesthetic (propofol) may be required because intubation induced bronchospasm may be related to an inadequate depth of anesthesia

Stepwise approach to treatment of perioperative bronchospasm according to the clinical presentation.