| |

Perioperative Fatalities Hit Anesthesiologists Hard Caroline Helwick |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

"The career-long prevalence of critical incidents is high for anesthesiologists," said Anahat Dhillon, MD, from the UCLA Medical Center in Santa Monica, California. |

| |

She presented the study results here at Anesthesiology 2012: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) 2012 Annual Meeting. |

| |

Nearly 70% of American anesthesiologists have experienced an intraoperative death during their careers. |

| |

It is estimated that 1 of every 13,000 perioperative deaths is related to anesthesia. |

| |

Dr. Dhillon and colleagues conducted their survey "to assess how many anesthesiologists have experienced perioperative critical events, whether they have an impact on their personal and professional lives, and what venues are available for debriefing." |

| |

The researchers invited 5000 randomly selected ASA members to complete a 17-item electronic questionnaire. |

| |

87.5% - reported a major intraoperative catastrophe |

| |

69.6% - reported an intraoperative death and 17.9% - reported a different type of critical event (nonfatal cardiac arrest, stroke, or myocardial ischemia).

|

| |

17.9% - reported a different type of critical event (nonfatal cardiac arrest, stroke, or myocardialischemia). |

| |

Physicians reported the following postevent effects: |

| |

|

Feelings of guilt (78.8%) |

| |

|

Difficulty sleeping (51.2%) |

| |

|

Feelings of isolation (28.2%) |

| |

|

Trouble concentrating (26.3%) |

| |

|

Change in appetite (14.7%) |

| |

|

Increased use of alcohol (6.4%) |

| |

|

Other self-medication (1.9%). |

|

| |

|

| |

"The increased use of alcohol is especially troubling," Dr. Dhillon noted. |

| |

Impact on Future Performance Impact on Future Performance |

| |

| |

|

The time to recover from these events varied widely. |

| |

|

Recovered in "less than 24 hours" (24%) or 1 month (16%), a significant number (18%) were "still recovering" at 1 year.

|

| |

|

71% said that the event had an effect on confidence in future cases, and 49% said it affected their performance in future cases.

|

| |

|

However, 96% of these physicians took no time off after the episode and 3% took less than 24 hours off, she reported.

|

|

| |

Supportive interventions were rare Supportive interventions were rare |

| |

|

Majority (70.0%) reported receiving "informal support" from family and colleagues, and 47.8% reported some "risk management" or "quality control" involvement. Only about one third received a debriefing from within their departments or from a multidisciplinary team.

|

| |

|

"Immediate support programs are likely to be welcomed, but they are rare," she said.

|

| |

|

"Trying to get time off is certainly difficult in our practices," Dr. Dhillon explained. "We feel pressure to continue on to the next case.

|

| |

Talking to the Family Talking to the Family |

| |

|

The anesthesiologist is not always involved in disclosing the incident to the family. Most of the time (93.7%) surgeons handled this, but in 57% of cases, anesthesiologists were involved in the communication.

|

| |

|

"Despite being a part of the perioperative team...anesthesiologists were not present at almost half these family debriefings," Dr. Dhillon said.

|

| |

|

Intraoperative deaths are a frequent reason for litigation. "The best means of preventing this is talking with the family, being honest and sincere, not giving conflicting information. When the surgeon provides information, then the anesthesiologist does so later, there is greater potential [for litigation]," she noted. |

| |

Ref: Anesthesiology 2012: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) 2012 Annual Meeting. Abstract A037. Presented October 13, 2012. |

| |

What To Do After an Adverse Outcome Frederic A. Berry, M.D. |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

The medico-legal system is not about truth – it is about society, lawyers and business.

|

| |

|

The Axiom of Medical Malpractice.

|

| |

|

“If nothing goes wrong then nothing matters.

|

| |

|

If anything goes wrong, then everything matters”

|

| |

Physicians reported the following postevent effects: |

| |

|

After an adverse outcome the anesthesia care giver will be enveloped in a 3-5 year period of stress, anger, frustration and depression. |

| |

|

The anesthesia care giver will need help during this difficult period. |

| |

|

This help needs to come from family, colleagues, lawyers and medical experts. |

|

| |

Algorithm for management of a Adverse Outcome Algorithm for management of a Adverse Outcome |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Immediate and long term management. |

| |

|

Recognize the emotional issues and deal with them. (Get help). |

| | |

Guilt, empathy, anger, depression. Guilt, empathy, anger, depression. |

| |

|

Be proactive in your own defense, i.e., literature searches, etc. Be proactive in your own defense, i.e., literature searches, etc. |

| | |

Listen to family, friends, colleagues, lawyers, etc. Listen to family, friends, colleagues, lawyers, etc. |

| | |

Continue or develop hobbies. Continue or develop hobbies. |

| |

|

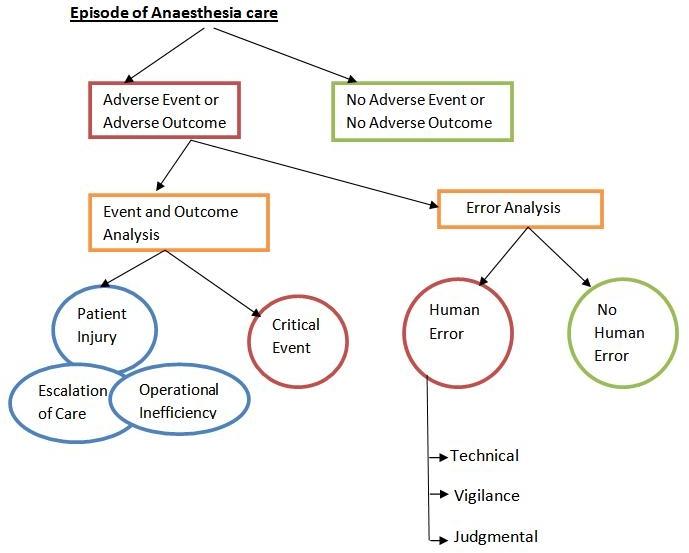

1. Adverse event – problems during patient care that caused or had the potential to cause an adverse outcome.

|

| |

|

2. Critical Incident – an adverse event that does not result in an adverse outcome is defined as a Critical Incident.

|

| |

|

3. Adverse Outcome – defined as

|

| |

| |

|

Patient Injury; |

| |

|

Escalation of care or |

| |

|

Operational Inefficiency. |

|

|

|

4. Human error – defined as a deviation from ideal performance in the areas of judgment, technique, or vigilance.

|

| |

KL Posner & PR Freund. Anesthesiology 1999; 91:839-47 |

| |

Disclosing Unanticipated Outcomes and Medical Outcomes |

| |

|

“Patients, and when appropriate, their families should be informed about the content of care, including unanticipated outcomes.”

|

| |

|

Patients experience two types of disappointment

|

| |

| |

|

The disappointing medical outcome. |

| |

|

The disappointing way the healthcare providers behaved afterwards. |

|

| |

|

“Research suggests patients are more forgiving of the first disappointment than of the second.”

|

| |

|

O’Connell

|

| |

Strategies to reduce the chances of an adverse outcome |

| |

| |

|

Refresher courses & CME meetings |

| |

|

Closed claims studies |

| |

|

Believe your monitors |

| |

|

Automated Information Systems |

| |

|

Policies & Procedures & Standards |

| |

|

The Angry Patient (Family) |

| |

|

Communicate |

|

| |

Definition of “Closed Claim” |

| |

|

When a medical malpractice claim is filed against a defendant a claim is “Open”.

|

| |

|

It is “Closed” when;

|

| |

| |

|

It is dropped. |

| |

|

It is settled. |

| |

|

It goes to trial and a verdict is reached |

|

| |

|

The goal of the Anesthesia Closed Claims is to identify major safety concerns, patterns of injury and strategies for prevention to improve patient safety by anesthesiologists working in pain management, operating rooms, labor floor, remote locations and critical care. Data is gathered in the form of detailed case summaries from malpractice insurance organization claim files.

|

| |

|

Four Most Frequent Themes

|

| |

| |

|

Believe your monitors! |

| |

|

Record keeping. |

| |

|

Surgical team agreeing as to what occurred. (Avoid rushing to condemn) |

| |

|

Communicate with patient before and after |

|

| |

Believe your monitors! |

| |

| |

|

Precordial Stethoscope. |

| |

|

Pulse Oximeter. |

| |

|

End-tidal CO2. |

| |

|

EKG. |

| |

|

Blood pressure. |

|

| |

End-tidal CO2 |

| |

| |

|

Ventilation with Mask and Bag. |

| |

|

Placement of LMA or ET tube. |

| |

|

Change in ventilation. |

| |

|

Accidental Extubation-LMA or ET tube. |

| |

|

A decreasing Cardiac Output. |

| |

|

If a CA occurs, adequacy of resuscitation. |

|

| |

The Medical Record |

| |

| |

|

Factual & short – this is not a dissertation. |

| |

|

Caveats & suggestions |

| |

|

|

Confer with nurses, etc. about sequence of events, times, etc. Sometimes notes and/or anesthetic record written hours later. State the reason in the record. |

| |

|

|

Recollection of events or corrections of errors are made in progress notes with the time, date and reason for discrepancy/correction. |

| |

|

|

No chart wars-if a mistake or different opinion go to the doctor or the nurse and discuss the issue- then to the administration. |

| |

|

|

Do not alter the record. |

|

| |

Record Keeping |

| |

| |

|

In 30 % of the cases I have reviewed better charting (Not perfect- but complete) would have greatly helped the defense of the case. |

| |

|

After every adverse event fill out the chart as if there would be legal action. |

| |

|

During “Adverse Events” often there is no time to fill out the chart-but do it later |

|

| |

|

Example: Record keeping

|

| |

| |

|

|

Patient for Arthroscopic shoulder surgery |

| |

|

|

Patient initially didn’t want Interscalene N.B. |

| |

|

|

Anesthesiologist records, “Pt does not want block.” |

| |

|

|

Surgeon tells patient that he needs a block |

| |

|

|

Block done, patient recovers with pain in neck, claims its due to block which was done” without my permission.” |

| |

|

|

Plaintiff wins case based on Chart. |

| |

|

|

Solution-“Patient agrees to block after talking with surgeon.” |

|

| |

Policies & Procedures & Standards |

| |

|

ASA Standards, Guidelines and Statements provide guidance to improve decision-making and promote beneficial outcomes for the practice of anesthesiology. The interpretation and application of Standards, Guidelines and Statements takes place within the context of local institutions, organizations and practice conditions.

|

| |

|

Standards provide rules or minimum requirements for clinical practice.

|

| |

|

Guidelinesare systematically developed recommendations that assist the practitioner and patient in making decisions about health care. These recommendations may be adopted, modified, or rejected according to clinical needs and constraints and are not intended to replace local institutional policies.

|

| |

|

Statementsthe opinions, beliefs, and best medical judgments of the House of Delegates.

|

| |

Ref: |

| |

|

Standards, Guidelines, Statements and Other Documents of the American Society of Anesthesiologists

|

| |

The Angry Patient/Family |

| |

| |

|

Find out why – now. |

| |

|

Empathize and clear the air |

| |

|

If still angry & hostile |

| |

|

|

If mad at you, let another M.D. to explain |

| |

|

|

If mad at Surgeon, let them clear the air. |

|

| |

Communicate-Surgical team and family |

| |

When Disaster Strikes |

| |

| |

|

Discuss with Team what happened: times, sequences, medications, etc. Document in Chart. |

| |

|

Talk to family with Surgeon & Risk Management* |

| |

|

|

Beware the guilt trip – “maybe I should have given blood sooner”, etc. |

| |

|

|

If a mistake has been made then admit the problem.* |

| |

|

|

If there is no evident reasons for the disaster say so. |

| |

|

Maintain contact with the family until closure. |

|

| |

|

*Be aware of what your insurance policy says.

|

| |

|

Contact insurance company – write a comprehensive note of the event. |

| |

Preparation for Deposition/Trial |

| |

| |

|

Review the medical record and depositions and know your entries. Do this immediately before the deposition/trial. |

| |

|

If you have any medical problems, i.e., HTN, DM, etc., see your M.D. before deposition/trial. |

| |

|

At deposition/trial |

| |

|

|

This is war – prepare accordingly |

| |

|

|

Make sure you understand the question |

| |

|

|

Short answers (You are not there to educate or convince plaintiff’s attorney of anything) |

| |

|

|

When you get tired – ask for a break. |

|

| |

Four Most Frequent Themes

Believing monitors Believing monitors

Record keeping Record keeping

Surgical team agreeing as to what occurred. (Avoid rushing to condemn) Surgical team agreeing as to what occurred. (Avoid rushing to condemn)

Communicate with patient before and after Communicate with patient before and after

| |

| |

Organisational approaches for the support of staff after a medical error has occurred The Swiss Foundation for Patient Safety |

| |

|

| |

|

The Swiss Foundation for Patient Safety has published guidelines describing the actions to take after an adverse event has occurred (for details see, www.patientensicherheit.ch). The following recommendations are a condensed summary of the advice offered by the Swiss Foundation for Patient Safety.

|

| |

Recommendations for senior staff members: Recommendations for senior staff members: |

| |

| |

|

A severe medical error is an emergency and must be treated as such (by being given absolute priority). It can have a severe emotional impact for the team involved. |

| |

|

Confidence between the senior staff and the involved professional, as well as empathic leadership, is an important prerequisite for the work-up of that situation. |

| |

|

Involved professionals need a professional and objective discussion with, as well as emotional support from, peers in their department. |

| |

|

Seniors should offer support for the disclosing conversation with the patient and/or the relatives and for further clinical work in cases wherein involved professionals might feel insecure in their daily work. |

| |

|

A professional work-up of that case based on facts is important for analysis and learning out of medical error. |

|

| |

Recommendations for colleagues: Recommendations for colleagues: |

| |

| |

|

Be aware that such an adverse event could happen to you. |

| |

|

Offer time to discuss the case with your colleague. Listen to what your colleague wants to tell and support him/her with your professional expertise. |

| |

|

Address any culture of blame either directly from within the team or by any other colleagues. |

| |

|

Take care of your colleague and be mindful of any feelings of isolation or withdrawal he or she may be experiencing. |

|

| |

Recommendations for healthcare professionals directly involved in an adverse event: Recommendations for healthcare professionals directly involved in an adverse event: |

| |

| |

|

Do not suppress any feelings of emotion you may encounter after your involvement in a medical error. |

| |

|

Talk through what has happened with a dependable colleague or senior member of staff. This is not weakness. This represents appropriate professional behaviour. |

| |

|

Take part in a formal debriefing session. Try to draw conclusions and learn from this event. |

| |

|

If possible talk to your patient/their relatives and engage with them in open disclosure conversations. |

| |

|

If you experience any uncertainties regarding the management of future cases seek support from colleagues or seniors. |

|

| |

Key learning points Key learning points |

| |

| |

|

Adverse events and medical error remain a common problem associated with the delivery of modern healthcare despite encouraging efforts to reduce them. |

| |

|

Every healthcare professional should be aware of the fact that he or she might face such an event at anytime during his or her career. |

| |

|

Open disclosure is a requirement not only of certain healthcare organisations like the Joint Commission of the Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAHO), but also an integral part of modern risk management. |

| |

|

The patient may not be the only individual to experience harm; support must also be offered to the relatives. Healthcare professionals directly involved in a critical incident also require support. These are the so-called secondary victims. It is strongly recommended that care and support is provided for these ‘secondary victims’, as the consequences of ill health encountered by work colleagues may be huge. |

| |

|

An open discussion with dependable trusted colleagues and seniors to analyse the adverse event conducted in a setting devoid of accusations and blame is mandatory. |

| |

|

A culture of trust must be implemented by the seniors and heads of the individual departments responsible for managing an adverse event |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|